[Partly edited December 8, 2008 and December

8, 2024]

20th Century Art, Music, and Literature

I've told you that one of the best ways to understand a

society is to look at the art, music, and literature it

produces. Looking at the Baroque style tells you a lot

about what is going on in the17th century. Looking at the

Rococo and Noe-Classical/Classical styles of the 18th century

tells you a lot about that time period. Looking at the

Romantic and Realistic styles of the 19th century also tells you

a lot about that century.

The artistic styles of the 20th century likewise tell you a lot

about that century. The problem is that their are dozens

of different styles and movements in the arts in the 20th

century, not just one or two that typify the century.

Nevertheless, regardless of style, one can point to three

particularly distinctive trends in much (though certainly not

all) 20th and 21st century art, music, and literature:

- A tendency to be less and less accessible to average

person

- A tendency to glorify art itself

- A tendency to undercut traditional standards and

values

As an example, consider the development of atonal music in

20th century.

Before the 20th century, serious music, even the

music of the greatest composers, was pretty easy for the

average person to understand and enjoy. Serious

music followed common and easily understood patterns (e.g., the

"I, IV, V, V7, I" harmonic pattern one finds frequently in

popular tunes).

In the 20th century, however, many of the most important

composers began to move away from these patterns toward what is

called atonal music. Atonal music is music without a home key.

There is a pattern, but the pattern is

not at all easy to recognize. Composers working in this

style prepare for themselves a 12 tone grid and then use the

grid systematically in producing their compositions.

[See this excellent video discussing

Schoenberg's method. Schoenberg's method is

sometimes just right for the theme. Here's Survivor

from Warsaw.]

[My son Michael put together an atonal piece he calls Sleepers Speak and Dance. A

challenge to the music majors: listen to the piece and see if

you can figure out why Mike gave the composition the title he

did. Looking at the

printed score makes things easier. One of the problems

with twelve-tone music is that, even a good musician often has

trouble understanding what's going on without the score in

front of them. ]

If one has an exceptionally good ear and special training, one

just might be able to hear the patterns in 12 tone music. But

Schoenberg doesn't even want you to be able to hear the

pattern. Obviously, this is music much less accessible to

the average person--and even to highly trained musicians!

How many people listen to and enjoy the music of Arnold

Schoenberg? Not many many. Even those that prefer

"serious" music to popular genres tend to listen more often to

the composers of earlier eras, to the Bachs, Beethovens, Chopins

and Mozarts rather then the Schoenbergs.

[But note that Schoenberg could and did

compose traditionally beautiful works--that get ignored!

You might enjoy Verklarte

Nacht.]

Twelve tone music also shows a clear tendency to glorify art

itself. What we are asked to admire here is the creativity

of the composer, his ability to find new ways to use the 12 tone

grid.

Also clear in atonal music is the tendency to undercut

traditional standards and values. The traditional idea was

that music should have pretty melodies and beautiful harmonies.

Composers, especially the Romantics, might occasionally use

dissonance (disturbing combinations of notes), but they did so

knowing full well that the effect was not particularly

pleasant. With atonal music, the situation is very

different. Playing a C and a C# at the same time creates

what would traditionally have been viewed as

dissonance--disharmony. Schoenberg said that this might

instead be what he called "distant harmony," and part of the

composers art might be to create a context where sounding a C

and a C# together is exactly the right way to complete one's

harmonic pattern.

Another 20th century composer working in the atonal style is

John Cage. Cage studied with Schoenberg and produced some

interesting 12-tone compositions of his own. But Cage went

on to develop another musical style, aleatoric music.

Atonal music sounds like random sounds even though it

isn't. Aleatoric music sounds like random sounds because

that's exact;u what it is! Cage

used many different methods to produce random sounds. He used

computers to generate random sounds, splashed paint over blown

up staff lines, etc. All this clearly violates the

traditional idea that music should follow a deliberate pattern.

If fact, Cage challenges virtually all traditional ideas of what

music should be. In one of Cage's compositions (4:33) the

composer sits down at the piano--and does nothing for 4:33!!!

Many other 20th century composers use the aleatoric style

is some passages, e.g., Igor Stravinsky in his Rite of

Spring. One critic described this work as "raw sound freed

from melody and harmony," what most of us would call

noise.

[ Is noise

music? Cage thought so. Here's a clip of Cage's Noise.]

In the

visual arts too one can see the tendencies I describe.

Typical of 20th century art is the development of Cubism by

artists like Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp.

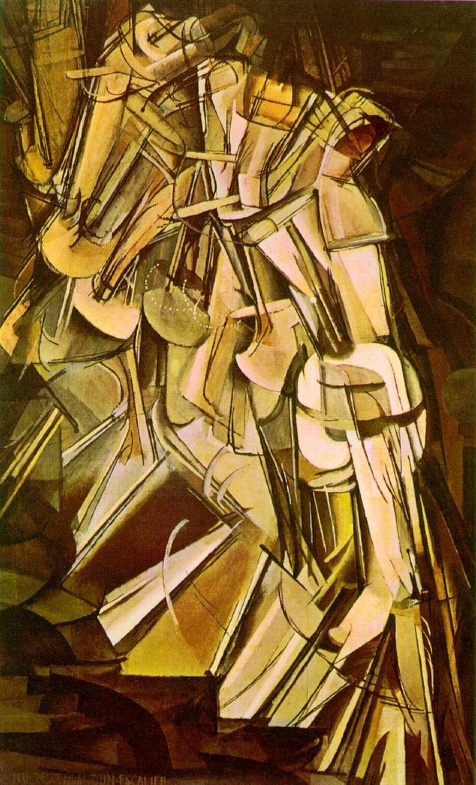

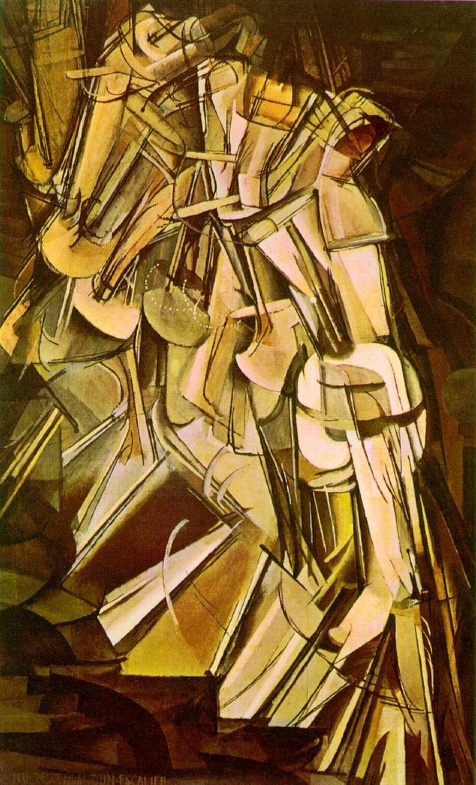

In Cubist art, the painter tries to combine multiple

perspectives, looking at an object from  different

points of view and sometimes at different times. Marcel

Duchamp's Nude Descending a staircase is a

good example. The painting is impressive in its

discovery of a way of conveying a sense of motion in a still

image. But the average person looking at a work like

this can't even tell what it is!

different

points of view and sometimes at different times. Marcel

Duchamp's Nude Descending a staircase is a

good example. The painting is impressive in its

discovery of a way of conveying a sense of motion in a still

image. But the average person looking at a work like

this can't even tell what it is!

The situation is even worse with a 20th century style

called Abstract Expressionism. In Abstract Expressionism

there are no recognizable objects. What we are asked to

appreciate is the artist's use of color, line,

composition. We get the expression of an artists

feelings--or (perhaps) the results of purely accidental

processes only partly under the artist's conscious control.

Soviet dictator Nikita Khrushchev described one

abstract work as looking like what would happen if a little

boy had done his business on canvas and spread it around when

his mother wasn't watching. And, to the average person--maybe

even to trained artists--this isn't so far from the truth.

There's an even greater challenge to traditional standards

of what art should be like in a style called Dada.

In Dadaist works (like those of Marcel Duchamp), there is a

deliberate attempt to eliminate all

previous artistic standards. Take a dead, stuffed monkey

(as did Francis Picabia). Label it on three different

sides "Portrait of Rembrandt," "Portrait of Renoir," and

"Portrait of Cezanne." And there's your work of art!

Draw a mustache and beard on a reproduction

Dada.

In Dadaist works (like those of Marcel Duchamp), there is a

deliberate attempt to eliminate all

previous artistic standards. Take a dead, stuffed monkey

(as did Francis Picabia). Label it on three different

sides "Portrait of Rembrandt," "Portrait of Renoir," and

"Portrait of Cezanne." And there's your work of art!

Draw a mustache and beard on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa

(Duchamp again),

give the picture a title with a semi-obscene double entendre (the

letters

on the bottom are pronounced "elle a chaud au caul")

and there's your work of art. Duchamp

here (and elsewhere) is deliberately trying to destroy

traditional ideas of what art should be like. "There's a great

work of destruction to be done." And the great tool of

destruction? Often, it's humor. See Duchamp's "Fountain"

(left).

of the Mona Lisa

(Duchamp again),

give the picture a title with a semi-obscene double entendre (the

letters

on the bottom are pronounced "elle a chaud au caul")

and there's your work of art. Duchamp

here (and elsewhere) is deliberately trying to destroy

traditional ideas of what art should be like. "There's a great

work of destruction to be done." And the great tool of

destruction? Often, it's humor. See Duchamp's "Fountain"

(left).

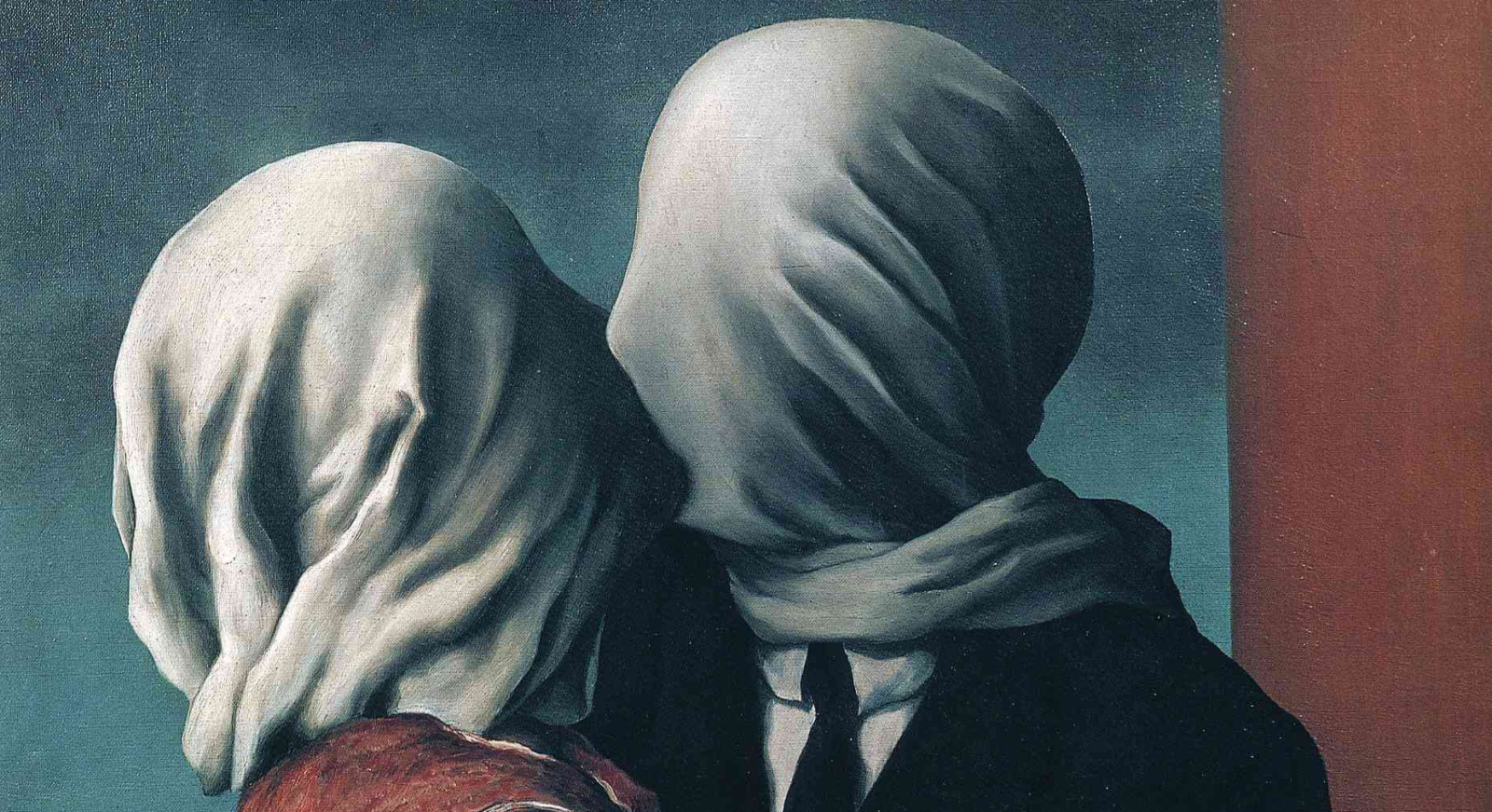

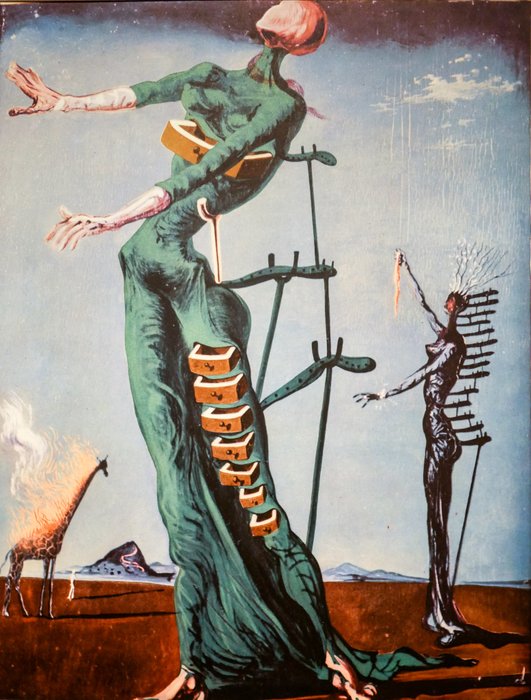

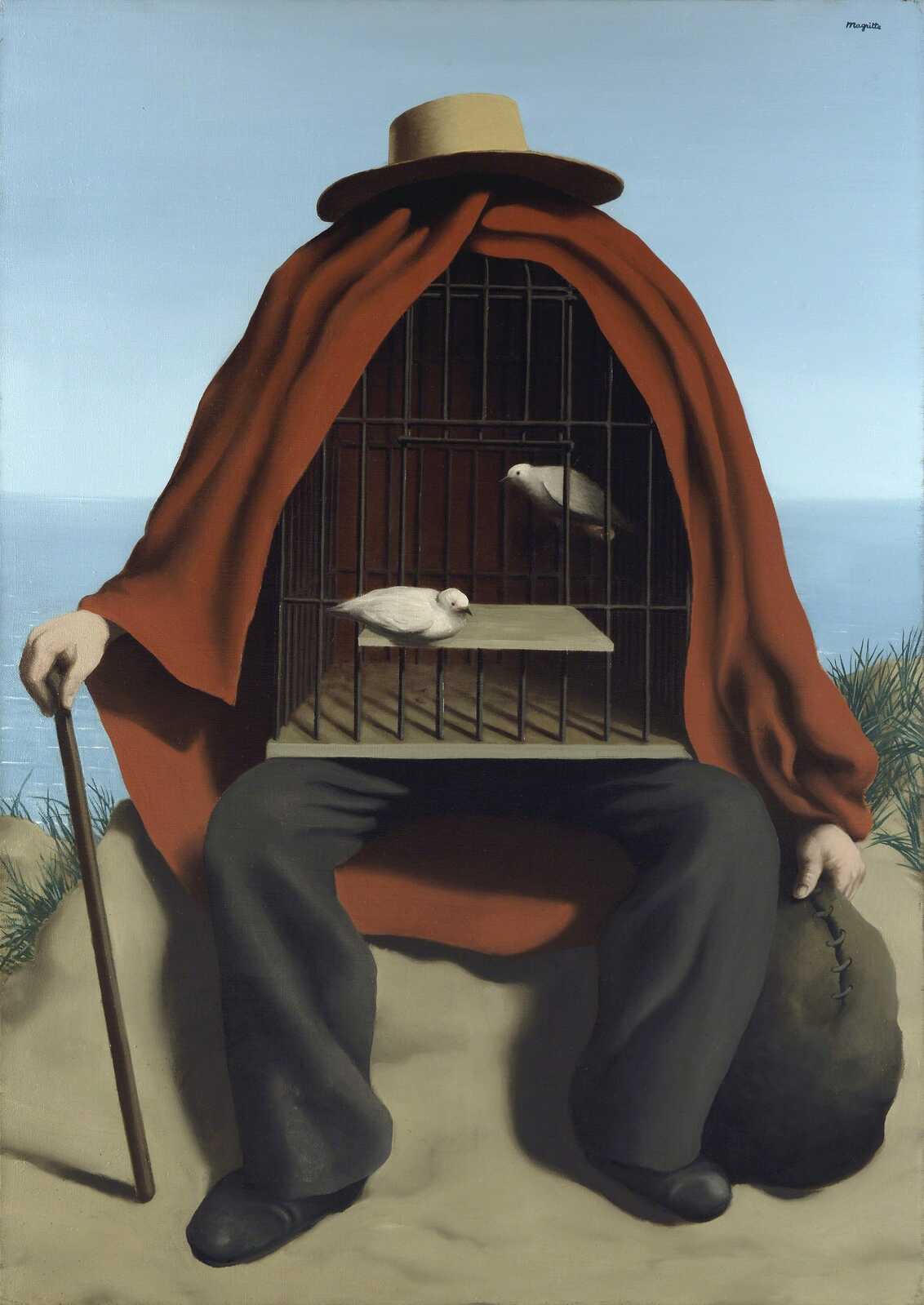

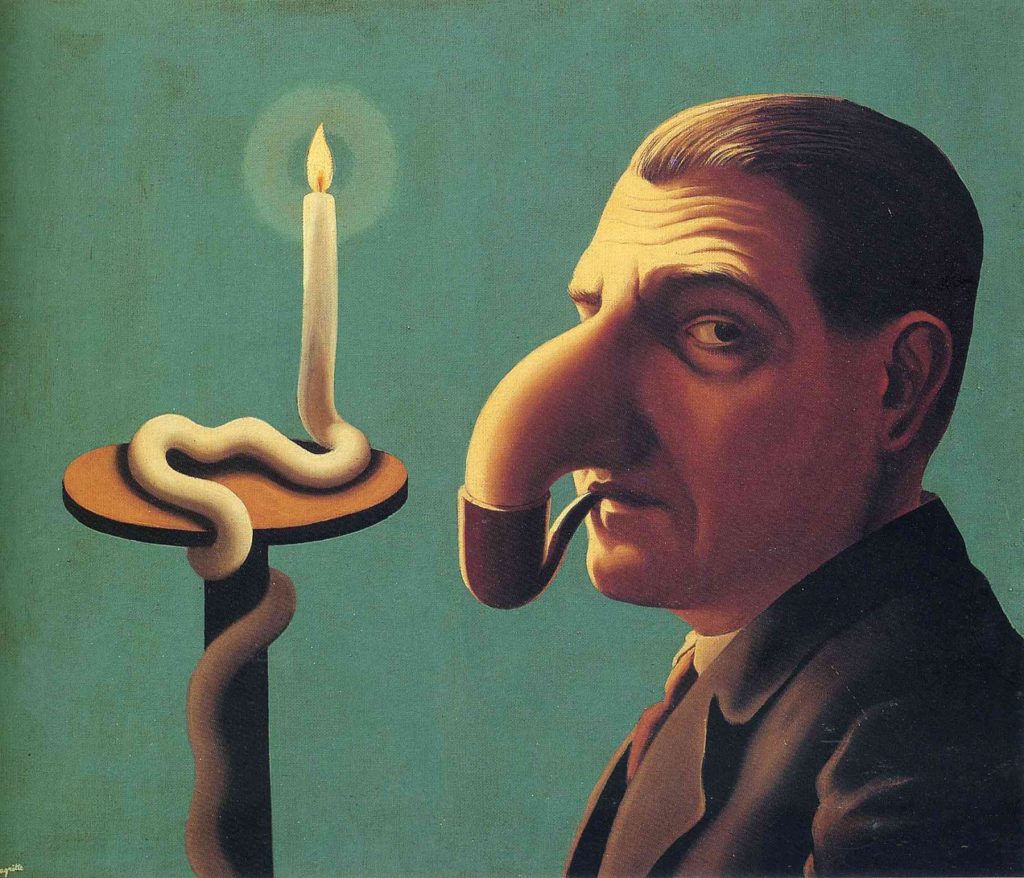

The Dadaist movement prepared the way for

another movement in the arts, Surrealism. Surrealism

is

a style, not just of painting, but of music and literature as

well. In some ways, Surrealism is

the best example of trends I talk about.

Surrealism's challenge to traditional standards

clear. The surrealists (men like Salvador Dali) say that

what the rest of us regard as reality

isn't truly reality. There is a deeper reality in the

subconscious mind, and true art should reflect that deeper

reality. Notice the twist: what most of us would consider a

distortion of reality is proclaimed by the Surrealists as the

true reality. Surrealists incorporate automatism and accident

rather than logical control as they create their artistic works.

Also, the Surrealists tend to emphasize things the rest of

us find disturbing in the extreme--and they tell us these these

things are good! Exceeding one's wildest imagination is

the goal here--and nightmare visions, because they are so wild,

are the epitome of beauty. "The

marvelous is beautiful," they tell us. "Only

the marvelous is beautiful." For Surrealists like Salvador

Dali, a flaming giraffe is beautiful. And Magritte's depictions

of a "healer," "a philospher," and "lovers? Beautiful!

At the opposite extreme, there is Pop Art, a style that gives

us, not unfamiliar images, but images that are as familiar as

they can possibly be. The most famous of the Pop artists

is Andy Warhol. Warhol gave us images from popular culture

transformed into art: Campbell's soup cans, Coke bottles, images

of Jackie Kennedy, images of Marilyn Monroe. The trouble

for us here is that it's hard to tell exactly what's going

on. What's Warhol's attitude toward popular culture.

Is he embracing it, or making fun of it? Is this simply a

continuation of Dada? Hard to say.

In most of these artistic styles there is a deliberate

attempt to shock the aesthetic sense, to produce something that

will challenge existing standards. In fact, in much modern

art, the only value in a piece is its shock value--and the more

shocking, the more likely the art world is to regard a

work as important. Robert Maplethorpe gives us pictures of

homosexual men in various sado-masochistic poses--and we've got

art. Andres Serrano gives us a crucifix upside-down in a

jar of urine: and we've got a work art. One recent exhibit

required viewers to walk over American flags in order to see the

other images.

This kind of thing was rare or non-existent in earlier artistic

styles which usually tended to reinforce religion, patriotism,

and traditional standards. Only in the 20th

century would such things be regarded as art.

20th century literature, too, reflects the trends I

mention above. An excellent example,

what's happened to poetry.

For most of human history, the works of the great poets were

easy for the average person to understand and enjoy. The

average person living in ancient Greece would have had no

trouble understanding and enjoying the works of Homer. The

average Roman would have had no difficulty understanding and

enjoying the works of Catullus, Ovid, or Virgil. The

average person of the Middle Ages would have had no difficulty

enjoying the Song of Roland. Clear up through the 19th century,

serious poets could be read and enjoyed by almost anyone.

In the 20th century, however, serious poetry took a turn away

from easy accessibility. Here's an example:

T.S. Eliot (1888–1965). Poems.

1920.

12. Sweeney among the Nightingales

APENECK SWEENEY spreads his knees

Letting his arms hang down to laugh,

The zebra stripes along his jaw

Swelling to maculate giraffe.

The circles of the stormy moon

5

Slide westward toward the River Plate,

Death and the Raven drift above

And Sweeney guards the hornèd gate.

Gloomy Orion and the Dog

Are veiled; and hushed the shrunken

seas;

10

The person in the Spanish cape

Tries to sit on Sweeney’s knees

Slips and pulls the table cloth

Overturns a coffee-cup,

Reorganised upon the floor

15

She yawns and draws a stocking up;

The silent man in mocha brown

Sprawls at the window-sill and gapes;

The waiter brings in oranges

Bananas figs and hothouse grapes;

20

The silent vertebrate in brown

Contracts and concentrates, withdraws;

Rachel née Rabinovitch

Tears at the grapes with murderous

paws;

She and the lady in the cape

25

Are suspect, thought to be in league;

Therefore the man with heavy eyes

Declines the gambit, shows fatigue,

Leaves the room and reappears

Outside the window, leaning in,

30

Branches of wistaria

Circumscribe a golden grin;

The host with someone indistinct

Converses at the door apart,

The nightingales are singing near

35

The Convent of the Sacred Heart,

And sang within the bloody wood

When Agamemnon cried aloud,

And let their liquid siftings fall

To stain the stiff dishonoured shroud.

40

What's going on here? Unfortunately, in order to

figure it out, you have to know extraordinarily well images

from classical literature and other sources--but, also,

details of Eliot's personal life. It turns out to be a

great poem, but how are we to know?

At least here we are left with some traditional

elements poetic elements: rhyme, meter, memorable

images. But what are we to do with poems that abandon

all these things, as much contemporary poetry does?

Well, we abandon them. 20th century serious poetry isn't

easily accessible, and so most of us give up.

And most of us have given up on serious novels as

well--or, at least, we've given up on some of those novelists

the English professors would tell us are particularly

important. One such, James Joyce.

James Joyce was a pioneer of what is called "Stream of

Consciousness" writing. Here's an example from his

"Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man."

Chapter 1

Once

upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming

down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the

road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through

a glass: he had a hairy face.

He was baby tuckoo. The moocow came down the road where Betty

Byrne lived: she sold lemon platt.

O, the wild rose blossoms

On the little green place.

He sang that song. That was his song.

O, the green wothe botheth.

When you wet the bed first it is warm then it gets cold. His

mother put on the oilsheet. That had the queer smell.

His mother had a nicer smell than his father. She played on the

piano the sailor's hornpipe for him to dance. He danced:

Tralala lala,

Tralala tralaladdy,

Tralala lala,

Tralala lala.

Uncle Charles and Dante clapped. They were older than his father

and mother but uncle Charles was older than Dante.

Dante had two brushes in her press. The brush with the maroon

velvet back was for Michael Davitt and the brush with the green

velvet back was for Parnell. Dante gave him a cachou every time he

brought her a piece of tissue paper.

The Vances lived in number seven. They had a different father and

mother. They were Eileen's father and mother. When they were grown

up he was going to marry Eileen. He hid under the table. His

mother said:

-- O, Stephen will apologize.

Dante said:

-- O, if not, the eagles will come and pull out his eyes.--

Pull out his eyes,

Apologize,

Apologize,

Pull out his eyes.

Apologize,

Pull out his eyes,

Pull out his eyes,

Apologize.

Now this is impressive stuff, a great way of (in this

case) presenting the earliest childhood memories of Joyce's

central character, Stephen Dedalus (who, by the way, is

basically Joyce himself very thinly disguised). But,

obviously, this is not the kind of stuff that is easy for the

average person! Even more difficult is Joyce's most

famous work, Ulysses.

In addition to showing the tendency to be less

accessible to the average person, Joyce's work shows the

tendency to undercut traditional standards and values.

The plot of Ulysses runs parallel to Homer's Odyssey, and

every character in the book has a parallel character in the

Odyssey. But the basic values are far different.

In the Odyssey, Penelope is the model of the faithful wife,

waiting 20 years for her husbands return. In Ulysses,

the corresponding character, Molly Blume, is anything but

faithful--and with Joyce's apparent approval. Likewise,

Joyce's "hero" (Leopold Blume) certainly isn't heroic in the

traditional sense.

Further, Joyce's work show's the tendency to glorify

art itself. In Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,

the young Steven Dedalus throws away his Catholic faith for a

new religion: the religion of art. For Joyce (and for

many other modern artists/writers) art really is a replacement

for religion, and we look to the arts for answers that people

once sought in religion.

Another 20th century writer using the stream of

consciousness style is Samuel Beckett. Beckett worked

with Joyce directly for a time (helping with Ulysses), and

then went on to write novels of his own, e.g., Molloy.

[See here the sucking-stone passage I talk

about in class.]

Beckett's novels are filled with events with no logical

connection. "Absurd!" says the reader. "Right!"

says Beckett. But life itself is absurd: much of what we

do has no meaning, and literature should reflect the

absurdities of life.

Beckett expresses even better his ideas on life in his

theatrical works, works like Waiting for Godot.

Waiting for

Godot is perhaps the most famous example of what is

called Theater of the Absurd. The two central

characters, Didi and Pogo, ramble on about this and that, and

there doesn't seem to be much logical connection to the things

they say or the things that happen to them. But then, in

the middle of the play there is a moment where we think we are

going to get clarity:

"Let us not waste our time in idle discourse! Let us do something,

while we have the chance! It is not every day that we are needed.

Not indeed that we personally are needed. Others would meet the case

equally well, if not better. To all mankind they were addressed,

those cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place,

at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or

not. Let us make the most of it, before it is too late! Let us

represent worthily for once the foul brood to which a cruel fate

consigned us! What do you say? It is true that when with folded arms

we weigh the pros and cons we are no less a credit to our species.

The tiger bounds to the help of his congeners without the least

reflection, or else he slinks away into the depths of the thickets.

But that is not the question. What are we doing here, that is the

question. And we are blessed in this, that we happen to know the

answer. Yes, in this immense confusion one thing alone is clear. We

are waiting for Godot to come—or for night to fall. We have

kept our appointment, and there's an end in that. How many

people can boast as much?"

"Billions"

What are we doing here? We are waiting for Godot to

come. Notice that Godot is GODot. We are waiting for

God--or, at least, a revelation of purpose of some sort.

But guess what? Godot never shows up. Message:

there's not much point waiting to find out the meaning of

life. You won't find the meaning of life because life has

no meaning. Bleak, bleak, bleak stuff--except it isn't, or

it isn't supposed to be.

Beckett subtitles his work a comedy in two acts (well, a

tragicomedy says Wikipedia). We are supposed to be

laughing. And that's what Beckett thinks we should do with

life. Since we aren't going to find any meaning in life,

all we can do is laugh at its absurdities. And do you see

how important art becomes from this point of view? It's

our artists and writers who point out the absurdities, help us

laugh at them and make life bearable.

Another master of the Theater of the Absurd style is Eugene

Ionesco. Both Beckett and Ionesco won Noble prizes, and

Ionesco's plays were particularly successful. As of April 2024,

The Bald Soprano

had a run of 67 years at Paris playhouse--the longest run in all

theater history.

One of my favorite Ionesco plays is "A Stroll in the Air."

At one point, the central character, a writer named Berrenger,

mourns the utter meaninglessness of life. He says he used to

take pleasure in saying that there was nothing to say, but that,

now he is so sure he was right, he can't even do that

anymore. Again, bleak bleak stuff.

But that's not the end of the play: it's the beginning!

Berrenger goes out for a walk, and ends up "strolling through

the air," essentially, flying. Ionesco's message:

when you see the absurdity and meaninglessness of life, don't

give up in despair. Take a leap--with your

imagination. And, once again, one sees how important the

arts become from this point of view. Since life has no

meaning, it's our imaginations that give us the most we can hope

to get out of life, and those people who inspire our

imagination--well, let's have a round of applause for them,

shall we?

Closely related to the Theater of the Absurd are the works of

existentialist writers like Jean Paul Sartre. Albert Camus

is my favorite of the existentialists, and I used to like

Heinrich Boll. However, the most famous of these writers

(and the one I talk about in class) is Jean-Paul Sartre.

In the years after World War II, Sartre was treated basically

like a rock star in France. His philosophical works,

plays, and novels were extraordinarily popular.

Eventually, he was offered a Nobel prize for literature--which

he turned down. His was surrounded by thousands of

admiring young people. What did he have to offer? A

special flavor of the existentialist philosophy.

There are several types of existentialism, but Sartre's brand is

what's called atheistic existentialism. It begins with the

idea that there is no God.

Now we have looked at atheistic philosophers already: Comte and

Marx, for instance. But Sartre differs greatly from

earlier atheistic philosophers in his attitude toward the

godless world. For Comte and Marx, the idea that there was

no God was liberating--a thing to be celebrated. For

Sartre, it was a very bad thing that there was no god. If

there is no God, there can be no universal standards of right

and wrong. If there is a God, what God says is right is

right, what God says is wrong is wrong. But if there is no

God, all ideas are subjective--and that makes our lives very

difficult. How can we know what to do, how can we confront

difficult ethical decisions if we have no objective standards of

morality? Sartre's version of existentialism seeks a way out of

this dilemma, offering a way of making moral decisions in the

absence of objective standards of right and wrong.

Sartre says that, before taking any action, we should look deep

within ourselves to discover where our own true values are, and

then should act accordingly. If we do this, we will have

acted in "good faith," authentically. If, on the other

hand we do not look deeply within ourselves or if we fail to act

in accord with that which is deepest within us, we will have

acted in "bad faith," inauthentically.

Now this seems a plausible philosophy of life, similar to

Polonius' advice in Hamlet, "This above all to thine own self be

true." But what happens when one tries to apply this

philosophy?

When I was in high school, I really liked Jean-Paul

Sartre--especially his plays. One of Sartre's books was called

"St. Genet, Actor and Martyr." It's about another French

writer, Jean Genet, a writer Sartre greatly admired. I

figured that, if Sartre liked him, Genet must be something

special. There were no Genet books in the library, so I

went to the bookstore and ordered a Genet book, "Our Lady of the

Flowers."

It's the only book I have ever burned. The book is filthy,

featuring the most degraded and degrading stuff imaginable. So

why did Sartre like it? Because Genet wrote about what he

*really* thought, what he *really* felt. Genet was,

therefore, "authentic"--and therefore good: good enough so that

we should call Genet a saint! Note the tendency to stand

traditional ideas on their head!

In Sartre's personal life, too, the existential philosophy led

to an inversion of the usual moral standards. As Sartre

looked within himself he saw a couple of things. He admits

that he is unable to love. He admits that, as far as sex

is concerned, incest appeals to him. His books and plays

often applaud incestuous relationships. And in his

personal life--well, Sartre had a long-time live-in girlfriend,

Simone de Beauvoir--his wife in everything but the legal

sense. Simone's young women students would often come to

their home--and Sartre would seduce these young girls one after

another. Horrible behavior in a conventional sense--but,

from Sartre's point of view he was acting "authentically."

He really wanted these girls, and so, the "right" thing to do is

to act in accord with what he just happened to find deepest

within himself.

[Simone de Beauvoir was the leading French

feminist writer of the time, and, when she died, French

feminists proclaimed that they owed her "everything."

Part of what they owed her a breaking down of the standards

women can expect from the men in their lives.]

Interesting also is the political philosophy Sartre's

existentialism leads him to adopt: Marxism. How is it that being

"authentic" leads one to adopt such a brutal philosophy?

My guess is that Marx, and many other modern artists and

literary figures, are drawn to Marxism because of their hatred

of the "bourgeoisie," and everything associated with middle

class values. An awful lot of modern art and literature is

an attack on middle class values, an attempt to shock the

bourgeoisie.

One example, a play we did at Stanford in the 1970's, Fernando

Arabel's "The Architect and the Empire of Assyria." The

play was designed to shock, featuring nudity, simulated

cannibalism, references to drinking urine and playing with

excrement, sadomasochistic priests, pregnant nuns, and

blasphemous lines.

But did it shock? Hardly. The audience, for the most part,

loved it.

"Shocking the bourgeoisie," a strategy adopted by so

many modern audience, didn't work in the way that they

intended. It did result in the breaking down of

standards: if the great "artists" didn't have to follow the

rules, why should anyone else? As the new standards

filtered down into popular culture, the mediocre, banal and

insipid was replaced but stuff that was equally mediocre,

banal, and insipid--and debasing at the same time.

This was not the way it was supposed to be. 20th

century artists musicians and writers did want to break down

traditional standards, but the idea was always that this

would be done to put up something better in their place.

And sometimes, artists have succeeded. But in too many

instance, this just didn't happen. Plenty was destroyed,

but what came out of the ashes wasn't always so good.

Instead, the result of many of these 20th century artistic

movements has been despair, perversion, suicide, misery--not

least for the artists themselves. You see, many of the

people I have been talking about, for all their talent, were

not very nice people, nor very happy people.

Pablo Picasso was a tremendous success--about as

successful as an artist can be. He had young women

throwing themselves at him, all wanting to sleep with this

great genius. Picasso was the kind of guy who likes a

cigarette after sex. And what he would do is that,

instead of reaching for an ash tray, he'd put out his

cigarettes on the body of the young woman he was

sleeping with.

Psychologically healthy men do not treat women like

this, and the absolutely awful way so many of the great

"artists" of the 20th century treated women is strong evidence

that they were not happy campers, and that there was something

seriously wrong in their approach to life. There seems

to be a wrong turn--and it's easy to guess exactly where that

wrong turn came.

Sartre wrote a short autobiography he called "The

Words." He describes his early years and his early

education in the Catholic schools of France. He once turned in

an essay on the Passion, the crucifixion of Christ. It had

delighted his family, but it was awarded only a 2nd prize.

He was disappointed not to be first, and said that this

disappointment drove him into prayerlessness. He

"maintained public relations with the Almighty, but privately

ceased to associate with him."

"Only once," says Sartre, "did I have the feeling he existed.

I had been playing with matches and burned a small

rug. I was in the process of covering up my crime when God

saw me. I felt his gaze inside my head and on my

hands. I whirled about in the bathroom, horribly visible,

a live target. Indignation saved me. I flew into a rage

against so crude an indescretion, I blasphemed like my

grandfather: 'God damn it, God damn it, God damn it.' He never

looked at me again.

This, it seems to me, is the wrong turn taken, not just

by Sartre, but by much of the 20th century. We live in a

society that has turned it's back on God, that thinks there's

something immoral and even illegal in talking about God. In

this class, many of you are uncomfortable whenever I bring up

religious subjects, and perhaps you think I'm doing something

wrong. But I want you to consider something

exceedingly strange about our society. I could stand up

before a class and swear like John Paul Sartre (God d----) and

nobody would bat an eyelash. I could stand up and

blaspheme like Arabel (God's gone crazy...). And nobody

would do a thing about it. But suppose I talked in a

different way about God.

Suppose, instead of saying god d--- all the time as so

many people on this campus do, I used phrases like, "Glory to

God", "Praise the Lord." "Praise be to God." I'd

get into trouble, wouldn't I?

Suppose I told you that you ought to love God with all

heart, soul, mind, and strength. I'd get into trouble,

wouldn't I? And suppose I told you that the only life worth

living was a life lived in obedience to the word of God.

I'd get into trouble.

And when my students come to me, as they often do, with

tears in their eyes over the latest tragedy in their lives,

carrying burdens so heavy that it breaks my heart--suppose I

told them what I would so much like to tell them about, a God

who knows every burden they carry, and wants to dry every

tear, and to give them lives of joy and peace and

happiness--I'd get into trouble, wouldn't I?

And if the shoe were on the other foot, as it so often

is, and after another dreadfully difficult day where I am

struggling to keep up, if I wasn't really up for a lecture,

and started class by asking students to take a few minutes to

pray for me, well, I'd get into trouble, wouldn't I?

And so I won't do any of those things. But I will tell

you this. Ideas have consequences. Every major

development in history begins with a set of ideas. The

French Revolution, the Holocaust, Stalin's reign of

terror--all began with ideas, ideas taught and spread in

university classrooms. Some of you are bored with ideas: but

remember that it makes a real difference which ideas win

out. And remember that, every time you step onto a

university campus, you are stepping on to a battleground--and

battle for student hearts and minds--and, perhaps, for their

souls as well.

Good luck on the final exam.

different

points of view and sometimes at different times. Marcel

Duchamp's Nude Descending a staircase is a

good example. The painting is impressive in its

discovery of a way of conveying a sense of motion in a still

image. But the average person looking at a work like

this can't even tell what it is!

different

points of view and sometimes at different times. Marcel

Duchamp's Nude Descending a staircase is a

good example. The painting is impressive in its

discovery of a way of conveying a sense of motion in a still

image. But the average person looking at a work like

this can't even tell what it is! Dada.

In Dadaist works (like those of Marcel Duchamp), there is a

deliberate attempt to eliminate all

previous artistic standards. Take a dead, stuffed monkey

(as did Francis Picabia). Label it on three different

sides "Portrait of Rembrandt," "Portrait of Renoir," and

"Portrait of Cezanne." And there's your work of art!

Draw a mustache and beard on a reproduction

Dada.

In Dadaist works (like those of Marcel Duchamp), there is a

deliberate attempt to eliminate all

previous artistic standards. Take a dead, stuffed monkey

(as did Francis Picabia). Label it on three different

sides "Portrait of Rembrandt," "Portrait of Renoir," and

"Portrait of Cezanne." And there's your work of art!

Draw a mustache and beard on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa

(Duchamp again),

give the picture a title with a semi-obscene double entendre (the

letters

on the bottom are pronounced "elle a chaud au caul")

and there's your work of art. Duchamp

here (and elsewhere) is deliberately trying to destroy

traditional ideas of what art should be like. "There's a great

work of destruction to be done." And the great tool of

destruction? Often, it's humor. See Duchamp's "Fountain"

(left).

of the Mona Lisa

(Duchamp again),

give the picture a title with a semi-obscene double entendre (the

letters

on the bottom are pronounced "elle a chaud au caul")

and there's your work of art. Duchamp

here (and elsewhere) is deliberately trying to destroy

traditional ideas of what art should be like. "There's a great

work of destruction to be done." And the great tool of

destruction? Often, it's humor. See Duchamp's "Fountain"

(left).